Edward Plantagenet (17 June 1239 – 7 July 1307) was the eldest son of Henry III, and despite being involved in revolts against his father, he was reconciled and supported him throughout the Second Barons' War against Simon de Montfort, and Edward became king when his father died in 1272. The only complication was that he was on his way back from Crusade at the time, and seems to have been in little hurry to return, so it was not until 19th August 1274 that he was crowned in Westminster Abbey.

Edward Plantagenet (17 June 1239 – 7 July 1307) was the eldest son of Henry III, and despite being involved in revolts against his father, he was reconciled and supported him throughout the Second Barons' War against Simon de Montfort, and Edward became king when his father died in 1272. The only complication was that he was on his way back from Crusade at the time, and seems to have been in little hurry to return, so it was not until 19th August 1274 that he was crowned in Westminster Abbey.

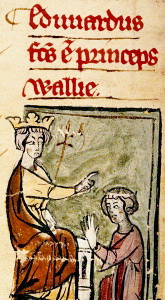

Persistent issues with the Welsh led to a full-scale conquest in 1282-83, and to hold this new territory a series of formidable castles were constructed to plant settlers in key areas and to keep the locals subdued. Many of these remain in good condition, and a visit to Conwy, Beaumaris or Harlech is highly recommended.

The death of King Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 offered Edward a further chance of expansion and a way to achieve the ambitions of his father, as the only heir to the throne was his three year old grand daughter Margaret, then in Norway. When Margaret died in 1290 on her way to Scotland, the Scottish nobility was left with a number of distant claimants to the throne, and a civil war looked inevitable. Instead, they turned to Edward for guidance, and he agreed to judge the relative merits of the fourteen Claimants to the throne. In 1292, he decided that John Baliol was the legitimate king, and Baliol was duly crowned at Scone on 30th November of that year, suitably on St. Andrews Day.

Whether Baliol had the better claim remains in dispute, with the suspicion being that Edward had in effect appointed a puppet who would rule in name only, rather than recognising the claim of Robert Bruce (5th Lord of Annandale, and the elderly grandfather of the man who would become king a few years later) who could perhaps have been a strong and independent ruler.

It therefore seems to have come as something of a shock to Edward to find that his puppet's strings were cut in 1295, when a council of Guardians was appointed by the leading men of the kingdom to "advise" their king, which in reality seems to mean that they took over and bypassed the ineffectual Baliol. Edward had no choice but to intervene again, and in 1296 he attacked with all his strength, defeating the Scots at Dunbar and eventually capturing Baliol at Montrose.

Having apparently resolved his problems in Scotland, Edward turned to his territories on the other side of the channel, and planned a campaign in Flanders, but his continual problems in financing his forces in Scotland and Wales had led to the imposition of a high level of taxation, and the country seemed on the verge of another civil war. His nobles had documented their grievances, in what became known as the Remonstrances, which were delivered to London at the same time as Edward left for Flanders with a smaller force than planned.

In Scotland, the background levels of resentment sparked into flame with rebellions against the English rule in several areas, including a major threat in the form of Sir Andrew Moray. Edward had left John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, in control in Scotland and in response to these stirrings of revolt he became increasingly drawn into military action. When Moray joined up with another rebel, William Wallace, the whole country seemed aflame, and de Warenne gathered a large force to subdue the revolt. The armies met at Stirling Bridge on 11th September 1297, where the Scots achieved an overwhelming victory.

Edward was thus presented with an opportunity to unite his kingdom in avenging this loss, and in 1298 he led his army in his first major battle since his prominent part in the Battle of Evesham in 1265. Deploying his archers and cavalry together in a masterly action, the Scots were cut down in their hundreds, and although Wallace escaped the field alive, his reputation suffered and he stood down from his position as Guardian.

However, Edward was unable to consolidate this victory, and by the end of the year the Scots were secure and had captured many of the castles which had been held by the English, the most important of which was Stirling.

Beset by financial problems, a nobility which was unhappy at the constant demands on their wealth and manpower, pressure from the Pope in response to successful lobbying by the King of France, Wallace and others, Edward was unable to follow up on Falkirk in any meaningful way. Campaigns in each of the subsequent years proved ineffectual, due to the Scots avoiding any direct confrontation and then raiding into England in return, but the balance of power seemed to be moving in Edward's direction with several of the leading Scottish nobles, including Robert Bruce, returning to his side.

The betrayal and capture of William Wallace in 1306 should have cemented Edward's hold on Scotland, but whether in revulsion at the mistreatment and public execution of Wallace or due to Edward's failing health, Bruce again changed sides and within months had murdered his main rival and had himself crowned King. Edward quickly dispatched another army to deal with the threat, but although this was initially successful Bruce emerged again in the following year and won a decisive victory at Loudoun Hill.

Edward stirred himself to lead an army in person, but camped within sight of Scotland at Burgh on Sands in Cumbria, he died on the 7th July 1307. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Despite being seen by many as a strong and successful king, Edward continually struggled to finance his ambitions and had substantial debts with several international bankers during his reign. Among many schemes to raise cash, Edward expelled the Jews from England in 1290 and confiscated all of their property. While this was not a new idea (having occurred in France and Brittany over fifty years before), it has left a long-lasting stain on his reign.